Insurance is not known as an exciting industry. It is big, slow, heavily regulated, complex, and lots of legalese.

But as far as exciting goes, there has been a fairly recent development in the space that is starting to gain traction.

Registered Index-Linked Annuities (RILAs) as the newest iteration of Indexed Annuities and have some pretty slick features.

A return that is linked to an underlying stock index

A known range of results

Some downside protection while giving some, all, or even leveraged upside

Tax advantages

It is definitely a product that can be a good fit in your financial portfolio that won’t get rekt in a market crash, but allow you to earn some good returns in up years.

And unlike many insurance products, many RILAs don’t charge any explicit fees, meaning no decaying of your returns over time.

RILAs were mentioned in last weeks post as a way to invest while offering some hedges in down markets and this week we will actually go into the details in how these products work and you can see if maybe they work for you.

[Reminder - every insurance company has their own product design. When it comes to RILAs you are going to want to compare the fees on a product, the investment options, and the ways each segment is structured. This post will talk in general about how many of the products operate, but you need to work with an advisor and compare products to make sure you find one that works for you.]

A Brief Evolution of Index Products

The first round of index products were not registered products. This means the investments couldn’t ‘lose’ money. (Note - if there were explicit fees on the accounts, your account value could go down, but the worst return you could get on your account was 0%.]

In both the annuity space (Indexed Annuities) and the life insurance space (Indexed Universal life insurance) the investment side worked the same.

You pay a premium to the insurance company and choose your investment strategy. The insurance company takes the money and puts it in bond investments. It then used the yield on the bonds to buy & sell options on an underlying stock index. Depending on how the index did, resulted in a return on the options which was then credited to your account.

For example, you give the insurance company $1,000 premium. The insurance company can invest in bonds that earn 5% return. The insurance company would then take $950 and invest in bonds. In 1 year that would grow to $1,000 again. This way the worst you could do on your investment was a 0% return.

With the $50 difference the insurance company would go and buy options on an underlying index.

There are 2 main strategies offered on indexed products:

Point-to-point with a cap rate

Participation rate

A point-to-point strategy with a cap rate allows you to match the stock index return up to the cap for that period in time. Let’s say you get a 1-year point-to-point on the SP500 with a 7% cap. This means you take the beginning and ending value of the SP500 price index (which ignores dividends), to see the return over the year at those 2 points in time. If the index returned:

Less than 0%, your options would be worthless and your indexed investment returns $0. Your AV would remain $1,000.

Between 0% and 7%, your options would match the index return.

So if the SP500 price index starts at $5,000 when you enter the strategy and goes up 5% to $5,250, you would earn a 5% return on your investment and your AV would be $1,000 + $50 return = $1,050

Over 7%, and you would hit your ‘cap’ so the options would pay off 7%

Your AV would be $1,000 + $70 return = $1,070

Participation rate is a pro-rata share of the index return.

If your par rate is 80%, your options would pay 80% of the return of the index.

So if the SP500 price index went up 10%, you get an 8% return on your strategy

If your par rate is 125%, your options would pay 125% of the return of the index

So if the SP500 price index went up 10%, you get a 12.5% return on your strategy

Note - Indexed products almost never have par rates over 100%. It can happen depending on market conditions, but most are in the 40-70% range.

No matter your par rate, if the SP500 price index returned a negative number, your strategy would pay 0% (remember, non-registered product means you can’t lose money on your investment).

Not too complicated. You would know every year what your cap or par rate was, and you would know your return could be in the range of 0% to the cap or 0% to some pro-rata amount of the index.

[Note- a ‘registered product’ is a regulatory term. If the investments of a life or annuity product can lose money, the agent that sells them needs to have additional credentials and be a registered agent. So variable products that invest directly into ETFs are registered. Fixed products that earn a fixed rate are not registered. Since regular indexed products can’t lose money, they are also non-registered.]

Now many of these products don’t charge the customer fees (some do, especially indexed UL life insurance). So how does the insurance company make money?

Remember we said you put $1,000 in and the insurance company buys $950 of bonds and has $50 to spend on options. Well that isn’t entirely true. Insurance companies take a ‘spread’. So maybe they earn 5% on the bonds, but take a 2% spread for their costs and revenue. So they really only spend $30 buying the options and keep $20 for their own selves.

Quick Note on the Option Purchases

I find this interesting as it is part of my job, but it isn’t important for you to know how the options work to understand the product from the customer perspective.

For a point-to-point cap product, the insurance company enters into a ‘bull call spread’. They purchase a call option at-the-money (the option strike price = current index price) and then sell a call option out-of-the-money (the option strike price is higher than the current index price and the at-the-money call).

If the insurance company has $20 to buy options with (option budget), and lets say the price of an at-the-money call is $30, it will buy that call. Then it looks up the option chain to see what option is trading at $10 and sell that option. Buy an option for $30 and sell one for $10 results in a $20 net cost which is your option budget. Whatever option is trading at $10 is where the company sets the cap. So if the option it sells is a 5% higher strike, the cap is 5%.

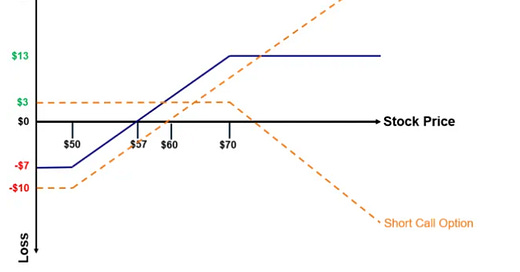

Visually it looks like this:

The X-axis is the stock price and the y-axis is the net profit on the option. In the above example, the at-the-money option it buys is at an $50 strike for $10 and the out-of-the money option it sells is $70 strike for $3.

The net cost of buying the $50 call and selling the $70 call is -$7

If the stock price is less than $50, both options expire worthless so the net profit is a $7 loss (cost of the options) for any stock price from $0 to $50.

At $50 the call your purchased starts to get in-the money, so for every dollar the stock price goes up, the option price also goes up $1

However at $70 stock price, the option you sold is in-the-money and starts costing you $1 for every $1 higher the stock price moves. At this point you have 2 options both changing the same amount for every change in the stock price, meaning it is a perfect offset. The most you make on the bull call spread is the option you sell.

For participation rate, it involves just buying at-the-money call options. So if the insurance company has $20 to spend, but the at-the-money call costs $30, it can only get 2/3rds. Meaning the participation rate would be 66.7%. However if the company has $20 to spend and the at-the-money call costs $15, it can get more than 1 call, and the par rate would be 133%.

Now that you understand a basic index product, we can get into a RILA which gives a LOT more upside to you by having you take a little of the downside.